28/03/2018

Listen to this talk on BBC iPlayer (UK only)

***

Read the transcript of the talk:

“He has not despised or disdained the suffering of the afflicted one; he has not hidden his face for him but has listened to his cry for help… the poor will eat and be satisfied… they who seek the Lord will praise him.” (Psalm 22)

About 15 years ago I was in a part of Africa which was in the midst of some very serious fighting. A group of black-clad militias was moving across the area – killing, looting, burning.

We were heading for a small town that we knew had been under siege. On the way there, after many hours driving on very bad roads, we stopped for a break. There was a series of burnt huts to our right, and I walked a few metres towards them.

Around me rose ash. It was about this time of year; in fact it was the Monday before Ash Wednesday. The ash rose in clouds, settling on me from the burnt houses. As I walked towards them I realised with a growing horror that the ash was from the bodies of people who had been burned.

That was ash without hope. Ash rising in clouds to cry out to all who saw it to witness the human evil that had taken place. And with no words or promise from heaven to make anything better.

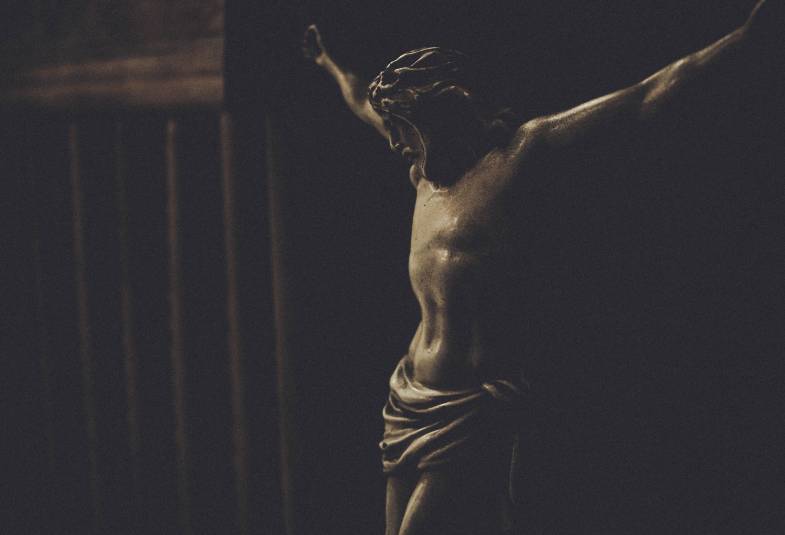

In the story of the crucifixion, there are no words ‘from heaven’. Instead we hear Jesus’cry on the cross: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” It is agonising in its pain and vulnerability. The words have resonated profoundly for millions of people down the centuries. The cry of Jesus speaks not just of his broken body; it speaks of his emotional distress. The betrayal of his friends. His sense of abandonment. The isolation of suffering when it seems like there is nothing and no one in the world but the present, terrifying moment.

There’s so much in the gospels about Jesus’ sheer humanity. He travels with friends, he walks, he tires himself out and crashes to sleep in a boat. He weeps, gets angry, laughs, and goes to parties.

But here on the cross, in his cry to God – which we call the cry of dereliction – this is his humanity at its rawest. This is where he connects with us most profoundly. It’s an expression of genuine emotional agony, together with overwhelming physical pain.

With the benefit of hindsight – and two thousand years of seeking to fathom what it means to speak of Jesus as God’s Son, as God himself – it can still come as a surprise to hear those words. After all, didn’t Jesus know this was coming? Hadn’t he been saying to his disciples for a while, “Things are not going to be easy. I will die at the hands of those who hate me.” And didn’t he know that ultimately he would be vindicated, raised from the dead? That it would all be OK in the end?

But of course, this is not how it works. Pain and distress are all-consuming for human beings. They out-shout whatever else our minds and faith might be trying to tell us. When we listen to Jesus’ cry, we cannot take this moment out of the context of his full, true human life.

So we cannot interpret his cry of suffering as surprise that God hasn’t intervened to rescue him. It’s not even that Jesus has misunderstood his purpose, or God’s love for him. That’s to over-think it. Jesus is fully human. So like the rest of us, it doesn’t matter what he knows intellectually: he is expressing his absolute agony, his complete vulnerability and sense of aloneness – felt at every level that pain can be felt.

And perhaps more than all those other qualities that made him approachable and yet holy, the vulnerability that we see most clearly on Good Friday tells me about the humanity of Jesus.

In a strange way, this vulnerability is not so different from that we see and celebrate at Christmas. At Christmas, we celebrate the Creator God who flings stars into space (as a well-known hymn puts it) but also chooses to put himself in the hands and at the mercy of the people he had made. This is the God who chooses to abandon power and control and become a small, vulnerable child.

It can be hard to understand that the God that I/they trust in can know such vulnerability and powerlessness. Yet Good Friday is where Christmas leads. The cross is what it means for God to have become human, and have chosen to work with his creatures. It means suffering the reality of oppression and anger and brokenness. It means experiencing the whole of what it means to be human – from birth to death – and all of the complexity, uncertainty and vulnerability that comes with that. It means there is nothing in our human experience that is too terrible, too dark, too painful for God.

So where does this leave us? Where do we go when we feel that darkness has overcome us, and we feel utterly abandoned by friends, family, and even God?

What happens here, on the cross, tells us that we need to take suffering seriously. There are times when we feel completely divorced from any love and companionship. We feel wrenched apart not just from others but also from God. Even if you have complete faith, as Jesus did, it does not protect you from the realities of human life – and it doesn’t mean you will always feel that God is there.

We don’t know always know where our suffering will lead, how things will end. The gospels suggest that Jesus did. That he knew not only suffering and death were lying ahead – but also resurrection and new life.

But here’s the thing about being human: the promise that we will “get through” tough times, that things will get better, that there is light at the end of the tunnel, does not take away from the agony of the moment. You still have to go through the darkness and the pain, and when you’re in the middle of it there is often no telling how long you’ll have to stay there for.

It’s no secret that one of our children suffers from depression and has done so for many years. There will be many listening who have experienced the pain of mental illness, either at first hand or through the experience of their family or friends, which can also, believe me, be debilitating. The darkness can feel absolute both for the sufferer and for those around them. “Darkness is my only companion,” says the Psalmist, describing such desolation. There are no shortcuts for us through that darkness, any more than there were for Jesus.

So here on the cross, Jesus does the only thing he can do – what he has been taught to do. He prays. Even though he feels abandoned, he reaches out to God and lays himself before Him. He doesn’t pray randomly, or with words made up on the spot. Jesus grew up learning the Psalms, those poems and prayers that form part of the Jewish and later Christian scriptures. He has come to know them so intimately that when everything else collapses and falls apart, he can grasp at words he knows that can give full expressions to what he feels.

I love the Psalms because they give voice to every human emotion you can think of. Yes, they are full of joy and delight and praise and wonder at God and his creation. But they are also full of pain and sorrow. They are full of hope and faith and trust in a loving God. They are full of anger at the injustice and pain of life – and at a God who does not always intervene.

No wonder then that this is where Jesus turns. He goes to Psalm 22. “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me? Why are you so far from helping me, from the words of my groaning? O my God, I cry by day, but you do not answer; and by night, but find no rest.”

Jesus is bearing the darkness of the world – its sin, horror and injustice, and human brokenness – and in so doing he is separated from the Father. The very act of working together in loving and redeeming the world tears God apart.

The rest of the story tells us a little more. The veil in the temple is torn from top to bottom. The sky goes dark for hours. It is as if God the Father is weeping and torn too, and Creation weeps in solidarity.

I think this is the other profoundly moving aspect of this cry from the cross: not just the pain of the Son torn from the Father, but the pain of God the Father torn from his Son, torn from himself. There is no part of God that is not touched by the cross. I even think of it as God’s first taste of death for himself. Jesus dies – and God grieves.

When suffering strikes, we often cry out to God as if God is somewhere out there. If we feel there is no reply it can seem as if God deliberately chose not to intervene, not to rescue. The cross tells us this is not the case. The cross tells us that God is intimately involved in our lives and suffers with us. It tells us that God chooses to change things the slow way – by getting involved with us, working with us and walking alongside us.

And that is what you learn if you read Psalm 22 to the end. Jesus only quotes from the beginning, but he would have known that this is not where Psalm 22 ends. The end is there, implied in Jesus’ quote. It starts with despair and anger and questions. It ends with an affirmation that God will come to the rescue, and bring justice and peace for all.

“He has not despised or disdained the suffering of the afflicted one; he has not hidden his face for him but has listened to his cry for help… the poor will eat and be satisfied… they who seek the Lord will praise him.”

The affirmation of God’s love and care is what makes it possible for the Psalmist, and Jesus, to start with despair and anger.

Precisely because they have known the care of God, they feel abandoned. Precisely because they have known his care, they speak out to him. Precisely because they have known that God is just, they are safe being angry and in pain before him. The Psalms of Jesus’ childhood have built faith in him that sustains even while it starts to stumble.

In times of darkness then, just like the Psalmist I argue and protest with God. I plead with him. Like the writer of Psalm 44, I yell at him to “Wake up!”

But that is not the same as a settled belief that God does not exist, or even any serious questioning about his reality. It's a moment of protest and arguing.

It's very much part of my normal prayer life, together with praise and wonder, delight and awe, petition and lament, celebration and rejoicing. The relationship we have with God is the deepest, realest, most unshakable we will ever have.

This life of prayer is shaped by the message Good Friday. There is no other message – none one other than: God is there. Wherever each one of us is: in light or darkness, in joy or pain. God is with you. I pray that you know the comfort of his presence – and joy as we move from Good Friday into the celebration of Easter.

This talk was first broadcast on BBC Radio 4 on Wednesday 28th March. Listen to this and other Lent talks here.