26/09/2016

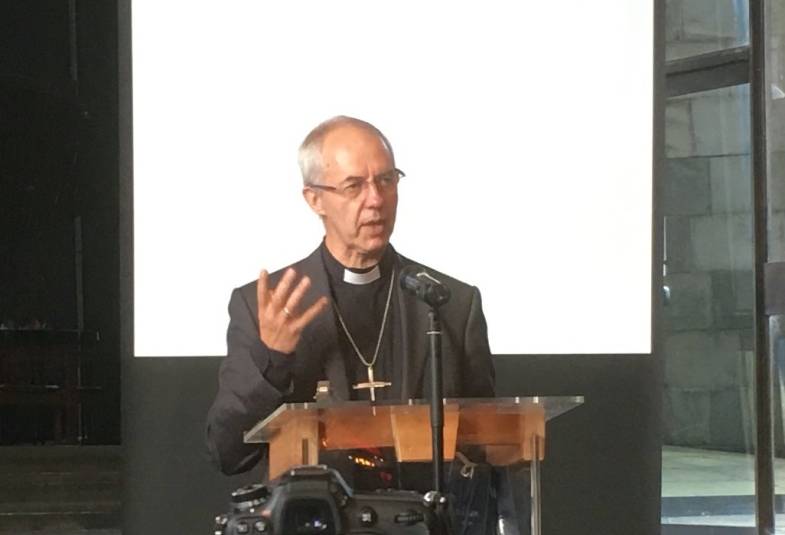

Read the text of the Archbishop's speech:

Church Schools: Communities of faith and reconciliation in a multi-faith context

When I last spoke on education it was 22nd June – the day before the vote on whether the UK remained or left the European Union. While it was only three months ago, as a country we are now in a very different situation, which will affect every aspect of life – including education.

It will certainly have an enormous impact, though we don’t know what, on the children you are educating. They are the generation that will probably see the biggest impact. Given that you’re secondary heads, your students are the generation where the impact on how we work, how our economy looks, how production is organised, how we go forward… will be hitting them as they come into the jobs market.

So I want to begin by identifying some of major issues that it seems to me impact – directly or indirectly – on the context in which you work as teachers and leaders.

They are issues that both support and threaten the fundamental purpose of education – that is to nurture people to live life in all its fullness. As you know, the vision for the Church of England education goes to John 10:10, and I’ll return to John 10 later in my remarks. The issues I’m going to talk about today are not a complete list, but they certainly impact, and can be shaped by, how we educate our young people.

I want to touch on Brexit, economic complexity, mental health and religiously-motivated violence.

As I said in the summer, the Church of England’s role as a major provider of education is core to the future of the Church of England. It’s something that has developed over more than 200 years. When I spoke in parliament a couple of weeks ago, I reminded people that we were doing this before the state was doing it. In fact the state took over from us. And when in this strange job I found myself in the House of Lords, my step-father told me, ‘you just need to remember that whatever you speak on there’s a world expert listening to you’. Which doesn’t reduce one’s level of nerves.

But on education we’re the experts. You are the experts. We’ve been doing it for 200 years. We have the corporate memory. We educate over a million kids, mostly primary of course but significant numbers of secondary, in this country. We’ve thought about it, worked at it, for so long.

Before the referendum, I believed - and I said publicly - that continued membership of the EU was in the best interests of the UK. However, the country has voted and with a clear majority that’s not the route we want to take. I don’t want to get embroiled in questions of what Brexit will mean for education policy per se – quite simply because at this time nobody has the slightest idea.

Rather, given the topic of this conference is the role of schools as agents of reconciliation, what Brexit offers today is a recommitment to educate children in a way that builds a powerful vision of what it means to be part of a global community. And one of the great dangers I think we’re facing is an inward-turningness – and many of the countries around the world in which the Anglican Communion operates, where I go and hear and listen and work, there’s this sense of turning inward, turning away from globalisation with its strengths and its weaknesses.

Some of the early analysis of what motivated people to vote to leave the EU – for example from the Joseph Rowntree Foundation[1] – talked about a lack of opportunities as a factor, and I’m sure that’s something you wrestle with every day, as students get towards the end of their school career. That sense, as I remember from many other places where I lived and worked, of people saying ‘Well there’s nothing for me. What am I going to do?’ And if you’re not in the areas of rapid growth and high prosperity, there really is a sense often of real frustration and near despair in some people.

In some circumstances the vote to leave was a recognition that the systems, economic and political that people were told to place their trust in, have not benefitted everyone in the way we were led to believe, and that includes schools and the church for that matter. The highly financialised and unfettered market economy creates both winners and losers. And those who feel like they have lost out were more inclined to vote Leave.

I am very clearly not saying that those who voted to leave did so because they were not as well-educated or knowledgeable. The point I want to make leads me to the second issue that I see as having a growing impact on how we prepare children and young people for adult lives that are to be lived to the full: increasing economic complexity.

There is a growing nervousness amongst many economists that the future of the global economy, and particularly the Western economies, is one that they call secular stagnation (secular in the sense of a long-term trend, not non-religious) that could last between 25 and 40 years. And it’s a narrative that is gaining growing traction.

It involves economies growing very, very slowly, and inequality growing very rapidly, because all of that growth is being concentrated in the top decile of society.

They may or may not be right, but the last time this really came to the fore was in the 1930s. Those of you who are economist will remember it dipping back down into depression in 1936-37, and the problem was only resolved by the massive spending caused by the Second World War, and that cost 60 million lives globally.

In addition to these global challenges, in the UK we’re likely to see significant shifts in demographics. This is one of the reasons, because it’s a global feature that the economists point to in secular stagflation, that the growing proportion of people whose consumption diminishes as they grow older – and where there’s less investment coming from those groups – constrains the world economy in investment terms. There will be a huge impact, as we know, on how the state supports elderly people.

Also there is the question simply of caring for an increasing proportion of elderly people. What will be the impact on our economy if the number of unpaid and unofficial carers increases dramatically? And more importantly, what will be the impact on our families, communities and society? How are people educated so they do not feel that their life is wasted if they spend a chunk of that life loving, caring for and valuing a human being who is unable to care for themselves? For the economists, that is a loss of output. In terms of the whole human being, it is a symbol of the love of Christ.

The Church must educate for a context where the economy has at least a 50-50 chance of not being the rapid-growth-and-employment kind of economy that has been the aspiration since the 1950s and the reality for much of that time. And where the economy is shifting and varying in what has to happen, far more than we’ve been used to in the past. We all know that for 20 years it’s been a cliché to say that people don’t have jobs for life. (Although a surprising number still do actually.)

But that has been the case. It seems quite likely, if we look at the fourth industrial revolution as it’s often called, that the shifts are going to be even more dramatic than we’re used to. Who drives a taxi if cars are driven by computer? What happens to all the taxi drivers? Just basic things like that. Who drives a bus, who drives a train, who flies a plane? I’m not that keen on being piloted by a computer, I have to say.

But the first ride in a driverless car was taken by the mayor of Pittsburgh earlier this week. Think through some of the impact of that on those who you educate who are not the really high-flyers in academic terms. It’s going to be very, very challenging.

I don’t want to paint an overly negative picture of the economic system now, or in the future. There are high levels of employment today, and we have a relatively very rich economy, even in the areas of poverty. I spend much of my time working in areas of extreme poverty, and with people coming from extreme poverty and areas of conflict – in sub-Saharan Africa, for example – and you realise the difference.

The UK is a hub of innovation and creativity, and that is something that must continually be nurtured in those who are being educated in our schools. That’s going to be a core value.

But all of this – both the positive and challenging aspects of our economy – reflects an incredible level of fluidity and flexibility in the markets, particularly in the labour market. So we must not allow the risks and challenges of an increasingly complex economy to drive and dictate how we educate. Because it’s very fluid and changing, there’s no point trying to predict it. But we must rather take initiative and show leadership in education. This means that teaching particular skills become less important than the capacity of the whole person to be someone who can adapt, develop, and be part of a community and society that we want. I will come back to this point in some detail a little later.

The third issue to highlight is that of mental health issues in young people – and I speak partly from personal experience; one of my daughters blogs regularly about mental health issues from her own experience of depression… we have a lot of familiarity with that in the family.

Data from the Understanding Society survey, which has been analysed in detail in the most recent version of The Children’s Society’s Good Childhood Report, suggests that mental health issues are becoming increasingly prominent in children and young people especially. One in 10 children and young people aged 5-16 suffer from a diagnosable mental health disorder - that is around three children in every class.[2] Eighty thousand children and young people suffer from severe depression – more than 8,000 of whom are aged 10 and under.

Those figures, although the most recently available, are also from some years ago and the numbers are likely to be higher today – not necessarily because the situation is worse, I don’t think people quite understand the causes, but certainly we’re better at diagnosis.

Mental health issues are not something that can be resolved simply by willing it to be so, or by being educated not to be affected by them. They are something that at some point are at a sub-rational point of the human psyche. But there is still a clear and important role for schools in providing support, and enabling children to grow through this. Offering a vision that is based on the human flourishing of all means creating communities where all feel equally loved, and where each child is recognised as unique and made in the divine image of God.

That is where our response must begin. What does that look like practically? It means creating space to raise awareness amongst pupils, parents and staff. It’s quite a challenge, with the pressures that teaching and support staff are under. The use of time for someone who’s showing signs of depression is really quite a burden.

Training for teaching and support staff to spot signs and respond. Treating mental health as a special educational need. Providing access to help, which will come especially from close links with the NHS locally. Being willing to advocate with and on behalf of those dealing with mental health issues. It means a holistic view of the young person and a holistic response – and church schools have the underlying values that take them to that better than anyone else.

The final issue I want to mention is religiously-motivated violence. For the first time for any of us, and in fact for our predecessors, for many, many years – since long before there was national education – the issue of conflict and of religion is generating a powerful and, indeed, at times uncontrollable and destructive influence in our society and around the world, to an extent that has put it at the top of the political agenda, and which affects the life of our own nation as well as abroad. No one before you in the last 10 years as secondary heads has had to face the kinds of issues with religiously-motivated violence since the 17th century to this extent.

It has come back, and that means religious literacy is essential to building the kind of society that we need in the future, whether you believe in the faith of a particular group or of no particular group. Religious literacy has become essential to understanding people’s motivation and ideas. That’s a new experience for all of us, and for our politicians, and for our education system.

There was a study published recently on jihadi violence and the underlying drivers of it, called Inside the Jihadi Mind. One of the things that comes out most importantly is that the heart of their theology – which is the heart of their propaganda, so this is the driving force – is an apocalyptic understanding of human history, not as a loose term but in its strictest technical terms: they believe that the world is about to end, that the Prophet will return with Jesus, and will defeat the western powers.

Now if you’re dealing with people for whom this is viable way of understanding the world around them, threatening to kill them is not – obviously – doing anything except confirming their analysis of the world around them. But what do you do when they are exceptionally and extraordinarily violent, as they are?

It’s very difficult to understand the things that impel people to some of the dreadful actions that we have seen over the last few years unless you have some sense of religious literacy. You may reject and condemn it – that’s fine – but you still need to understand what they’re talking about.

The second thing I want to say about religious literacy is that we need to shift the current mind-set – in education policy and public policy more broadly – around religion from a “prevent” narrative to a “vision” narrative. . .

We have to offer an alternative vision that is more convincing. That is more profound. That is more satisfying to the human spirit. And where to do we find a better vision than in the gospel of Jesus Christ, in the good news of Christ? And that’s where you come in.

The Church of England is driving forward with implementing this vision. I’m sure that you will have read the new Church of England vision for education, Church of England Vision for Education: Deeply Christian, Serving the Common Good. It is a profound piece of work and one that I wholeheartedly commend. It offers a values-based vision that is deeply and authentically Christian, but inclusive and embracing of diversity.

As I have already said, the heart of our vision for education is Jesus’s message in John’s Gospel, chapter 10 verse 10. Jesus says, ‘I came that they may have life, and that they have it abundantly’. And so the vision starts with the concept of what we mean by ‘abundant’ life for those who are being educated in our schools.

Much of what the vision sets out is already done to a very high degree of success in many, many Church schools. But the value of releasing a document like this now – particularly as we are aware that further education reform is very much on the Government’s agenda – is that it anchors everything that Church education is about in a clear, challenging and Christ-centred ethic. As the vision states, “there are four basic elements that run through the whole approach”, which together “form an ‘ecology’ of the fullness of life”.

I want now to look at each of them briefly, in relation to the four challenges I have already set out, to give a sense to how they can be applied to the context in which you are educating and to put meat on the bones of the central question, ‘what are we educating for?’.

First, we are educating for wisdom, knowledge and skills.

I have already talked at some length about the increasing complexity, fluidity and flexibility of our economy and markets. While a vision for education – particularly one based on Christian theology – must avoid at all costs reducing the individual to an economic unit, it is clear that good schools must “foster confidence, delight and discipline in seeking wisdom, knowledge, truth, understanding, know-how, and the skills needed to shape life well.”[3] We must be doing everything we can to ready young people to be prepared to face a complex world, and one that is very different from the one we currently live in. Providing them with the academic capabilities, creativity and emotional intelligence that an ever-more complex world demands is vital.

We are also educating for hope. As the vision states, “in the drama of ongoing life, how we learn to approach the future is crucial”, which strongly relates to what I have just been saying. Hope and aspiration are also important paramount in working with children and young people with mental health issues. They can be a healing force against issues of depression and anxiety. Teaching in a way that assures that “bad experiences and behaviour, wrongdoing and evil need not have the last word” – which is at the centre of what we believe as Christians, because God raised Jesus Christ from the dead; death did not have the last word – can be transformative. Offering “resources for healing, repair and renewal” – how many of our children don’t need repairing? How many of us don’t need repairing? Most of life is about learning how to be repaired well together – and teaching that “meaning, trust, generosity, compassion and hope are more fundamental than meaningless, suspicion, selfishness, hardheartedness and despair” will help change the lives of young people.

Educating for community and living well together goes to the root of my comments about religiously motivated violence and religious literacy. Church of England schools are not cosy clubs for Anglicans, but a blessing for every child in the community they serve.

I recently heard a colleague tell this story, which I think sums up very nicely the perception that some may have of ‘church schools’. A rabbi goes to the barbers for a haircut. At the end, he went to pay but the barber wouldn’t accept his money. "No, rabbi,” he said. "I never take money from the clergy”. The following morning when the barber got to work there on the steps of his shop was a bag of delicious newly baked bagels. The following day a Catholic priest went for a haircut. At the end the barber wouldn’t accept any money. "No father,” said the barber. "I never take money from the clergy.” The following morning, there on the steps the barber found a large bottle of whisky. The following day an Anglican vicar went to have his haircut. At the end the barber refused his money. "No reverend,” he said. "I never take money from the clergy.” And the following morning there on the steps the barber found an enormous queue of Anglican vicars. [Laughter]

We are operating in an environment, particularly when it comes to education, that views church schools with suspicion and we must be alert to that. While the statistics are clear that Church of England schools are increasingly moving away from selection on the criteria of faith, and increasingly diverse, as the Vision sets out, “each school is to be a hospitable community that seeks to embody an ethos of living well together”[4]. To do this, “education needs to have a core focus on relationships and commitments, participation in communities and institutions, and the qualities of character that enable people to flourish together.” This is a moment for church schools to lead the way on challenging all forms of sectarianism, faithfully and confidently, and in the knowledge and comfort of Jesus Christ’s command to not be afraid.

The fourth and final element is educating for dignity and respect. Central to Christian theology is the truth that every single one of us is made in the image of God. To cause the dignity of a person to be undermined is to disregard this fundamental truth. One of the Church’s deepest failings – again another heart-breaking thing for me – has been to fail to protect children and vulnerable adults from harm and abuse. It’s this failing that makes our safeguarding more important than ever.

In the Church of England we’ve also tried to improve the Church’s lamentable background on issues around LGBT, with the launch of a programme, about 18 months ago, when we realised that the level of homophobic bullying and the level of mental illness amongst children are very, very closely correlated and caused. So human dignity is something we’ve got to show in practice on the ground, by tackling that kind of issue, as well as abstractly.

Educating for dignity and respect is about being both deeply and authentically Christian but also, as the Vision puts it, “encourages others to contribute from the depths of their own traditions and understandings.” Without this, we cannot hope for our children and young people to be able to demonstrate such values themselves in the future.

In conclusion, I feel we are faced with three challenges.

The first is to be confident in Christ. There is an increasing demand for authenticity and to shy away from the deep and authentic Christian foundation of our schools would be a costly mistake. We need to be faithful and confident in how we approach this in schools – particularly in the context of collective worship in increasingly multi-faith schools. At its best collective worship can be about deep and significant participation in a community – which is fundamental to all of what I have spoken about this morning. When I was in Chesterfield in June, I witnessed some of the most profound and inspiring collective worship that I have ever seen. It was led entirely by pupils and was authentic and deeply moving.

I want to encourage you to continue to look for new ways to do collective worship. A wonderful way to boost the spiritual development of young people is to encourage them to experience and be involved in pilgrimage. Some schools already go to Taizé each year, but the CofE Education Office are hoping to get at least 50 secondary schools (preferably more) to commit to going in 2018. This is a very exciting initiative and I very much hope that you will consider that opportunity, because it will have a profound impact on children’s spiritual development.

The second challenge is to be willing to constantly reflect on where your school is succeeding and where there might be opportunities for innovation, particularly in the context of the changing landscape we find ourselves in. The newly launched Church of England Foundation for Educational Leadership will play a central role in helping develop creative and innovative school leaders who can do exactly this. Regional pilots and training opportunities are being launched from this September and I strongly encourage you to get your schools involved. The Foundation is an example of visionary leadership from the Church of England in education policy, and I’m delighted that its work will be accessible to all leaders in education, whether they are working in Church of England schools, community schools or at a system level.

The third and final push is to show your support for the Church’s commitment to open more free schools. We have heard this month from the Prime Minister that she is supportive of the growth of free schools, and particularly in areas of social and economic deprivation. There is a prophetic and potentially transformative role for the Church of England to play here. Many of you will already be looking at how you might be able to get involved. I want to encourage all those secondary schools present to try and clone yourselves – because you do an extraordinary job. You’re very, very good at what you do and we need more of it. Imagine what a difference another school in your area would make. Let us aim to be so successful that we can’t do everything that is asked of us by local and national government. (We’re getting close to that already, to be fair.) We have a huge opportunity to shape our education system for good – I mean, for the good – and I hope that you will share my enthusiasm and optimism for the task at hand.

We are in a time of profound uncertainty in both the short and long term outlook. In such times our rock is Christ, and our hope is to rest on Him. When we do that we are able to be adventurous and to reach out powerfully without losing the sense of who we are. If our Church schools provide that adventurous spirit, that hopeful journeying, together with the high levels of technical and humane education that have been your great characteristic, we can shape the future of our country.

Education is the most important area of the Church’s work in society. Educating a million children a day, we have the opportunity to create communities who default is the common good – to human flourishing, wisdom, hope, community and dignity. I pray for strength, for courage, for wisdom as you seek to do this, and my God bless you richly with his love and peace today and in the months and years ahead.

[1] Matthew Goodwin and Oliver Heath (2016) ‘Brexit vote explained: poverty, low skills and lack of opportunities’ https://www.jrf.org.uk/report/brexit-vote-explained-poverty-low-skills-and-lack-opportunities

[2] Green, H., McGinnity, A., Meltzer, H., et al. (2005). Mental health of children and young people in Great Britain 2004. London: Palgrave.

[3] The Church of England Education Office (2016) Church of England Vision for Education: Deeply Christian, Serving the Common Good, p9