08/01/2020

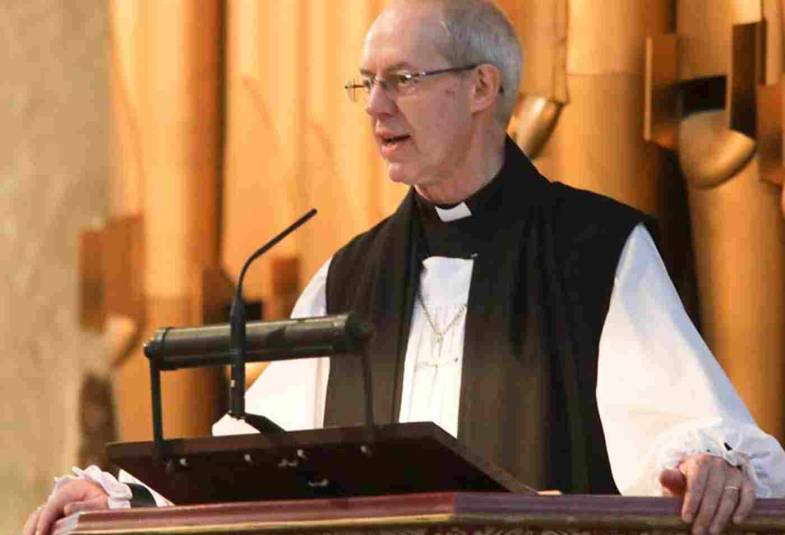

Archbishop Justin Welby preached this sermon today at the Service for the Opening of the New Parliament at St Margaret's Church, Westminster.

Isaiah 60:1-6; Ephesians 3:1-12

Oh Lord our God open our minds afresh to the light of your love, and to your grace, to the beauty of your care for this world and for us, that we might be strengthened in your service. Amen.

Well since I was last in this pulpit, they’ve repaired the clock. I remember it didn’t move which was sort of good news for me, but bad news for you. Unfortunately, it now appears to be moving quite swiftly.

It is a great privilege to be with and a great privilege to be asked to speak at this service and I’m particularly grateful to the Dean for allowing me to be here.

This is of course the first time that I have been in this church with you, Mr Dean, since you arrived.

Elections are reconciled civil war, the carrying on of the allocation of power by better and more civilised means than in the past.

By the grace of God, we have reached a point where we don’t do changes of power as we did in the seventeenth century, with battles and death, but with integrity of process and proper questioning of those seeking office.

On that at least I hope we can agree. We are a country that is blessed by its democracy. It is not perfect, but it gives us freedoms and choices that we can exercise at least every five years.

Yet with all the emotions present after an election – the celebration and the depression, the hope and the despair, the concern and the ambitions; all emotions that are reasonable, human, understandable emotions – what do we say?

As Christians, and in fact from all the major faiths represented here today, we say that whether we are content or dismayed we seek God’s blessing on this country of ours.

Not its blessing in the sense of others’ impoverishment or defeat as though the world was a zero sum game, or as though the country was a zero sum game, but its blessing in a way that makes the UK a blessing to the world, because it has received blessing.

A blessing to even to those with whom we disagree most profoundly. For in blessing others we ourselves will be blessed.

What naivety, what innocence; but then that’s my job. What a lack of realpolitik.

Well unfortunately for those who believe it is realpolitik that governs our future, the scriptures say something completely different. Look back at the Old Testament reading from Jeremiah.

The people of Israel had gone wrong in a popular policy – I’m not making a comment on the election in any way at all, just in case there is any doubt about that. I have gone through the sermon again last night looking at how I could be misunderstood, and I’ve taken out most of it.

But the alternative is to stand up here and say wouldn’t it be nice if we were all nice. I’m going to resist the urge, not least because that would be nice for you, because it would be short, I love listening to myself.

The people of Israel had gone wrong in a popular policy, a policy supported by leaders and led by prophets and priests. They had been led into defeat in war against the Babylonians.

They had gone to Babylon in what today we would call a death march. The survivors in Babylon had written to Jeremiah to ask what they should do now.

Their prophets in exile among them in Babylon had said it was only temporary. Yes, they had lost the war. Yes, Jerusalem had fallen. Yes, the leadership had been taken away and many killed.

But God did not change and God, unchanging, would swiftly fulfil his promises and bring us back to Jerusalem and to the defeat of Babylon.

At this time of pantomime season one can summarise Jeremiah’s response in the words, “Oh no he won’t.”

Jeremiah was deeply unpopular. He was now saying that the Babylonian rule would last for seventy years. That few if any of the current generation would live long enough to see its end.

He told them to bless the city of Babylon, to enable it to prosper, to settle there, to marry, to give in marriage, to build houses, to plant gardens.

Imagine if this country were occupied by an enemy and the Archbishop of Canterbury, instead of calling for resistance and victory, said: “Settle down and bless them.” Our minds recoil at such treachery.

But Jeremiah is saying to them that it was their breaking of the covenant with God that led to this disaster and they now must keep their covenant with God by seeking the blessing of their foes, their conquerors.

It is a call echoed in Jesus’ most challenging words: “Love your enemies.”

Paul, in the second reading, in his letter to Ephesians writing from prison, uses the word “mystery” to mean something hidden for ages but revealed through Jesus Christ and the work of the Holy Spirit in the Church.

A mystery is not a baffling puzzle, but something that is unveiled. Seventy years after Jeremiah wrote, people began to understand what they had gone through and why they had gone through it, this time of exile and suffering.

The mystery was revealed then in a new society. The mystery of God is revealed to us in the apparent disaster of the cross.

So, what does that say to us? That the call of people of faith in our parliament is to persevere in seeking the blessing of the country.

That may mean unpopularity. It will certainly mean disagreement. We believe as those of faith, and as Christians, we believe in absolute truth.

We believe certain things are good and certain things are bad regardless of whoever says to the contrary.

We believe there is absolute virtue and absolute evil and we need to know how not to be relativists.

Certain things are, in the traditions of Christian teaching, in the scriptures, in the mind of God, in the beginning, and in the life of Jesus, absolute goods: families and households; care for the most vulnerable, economic justice, the love for the stranger.

To support such things, from any side of politics, simply because the scriptures show they are close to the heart of God in Jesus Christ, will lead to disagreement.

Not only disagreement about what is right but, even when we agree on what is right, how we carry it out.

The character of disagreement, the means of achieving blessing for all of our country and beyond, rightly includes fervent and robust argument – but never hatred. Because you cannot bless those you hate.

Our disagreement, our perseverance in seeking blessing, must be done with love, even for those who seem enemies – even for those who genuinely are our enemies – for that is how Christ loves us.

That is the mystery that Paul unfolds. It is the mystery to which Jeremiah points and prophesies. It is the mystery of God’s love, that God reaches to those who were his enemies.

None of this is easy, and none of it always feels like a blessing. Some of it seldom feels like a blessing.

Yet it is in obedience to seeking blessing even for those we disagree with that we most clearly resemble the God we claim to worship.

It is in seeking the flourishing of our country – of every part – that we most nearly capture the image of Christ in his abundant and unconditional liberality of love and grace.

It is in seeking the blessing of the world in which we live, and in which the UK still has so much influence, that we testify to our Christian heritage.

To bless opponents, even enemies, is never easy. Within the Church my constant prayer, early morning by early morning, is to remind myself that those who disagree with me, and use vituperation and insult on social media (and many of you have had much worse), are those to be loved and blessed.

I wish I was better at it. But I know that I can only be like Jesus when I face those who disagree, listen to them, seek the grace of God to love them, pray for them daily, even when those prayers – if I’m transparent and honest – are forced out through gritted teeth, and persevere in doing so.

More than that, collectively we can only be a blessing, find the strength to bless when we are with others in so doing. When we come together as the people of God, as today.

If we stand alone or get into our little cliques, whether in church or in politics, elation and triumphalism will overcome us in victory; dismay and despair weaken us in defeat.

When we act as the body of Christ and work together, praying with those with whom we disagree – as well as for them – the Spirit of God strengthens us collectively to be a blessing.

And when we pray for the blessing of country and of each other, then we find the grace and wisdom of God lifts our hearts and minds to a new vision of what it is to be the people of God. Of what it is to be a country that is blessed in a world that that country blesses.

We may not agree with all that we are alongside, but we will love. In so loving we will reveal the purposes of the mystery of Christ, rise to the challenge of love and know more deeply his love for us. Amen