07/01/2020

This blog is written by a member of the independent Commission. These views do not necessarily represent the views of the Archbishops' or the Church of England.

Shieldfield in Newcastle is literally being wiped off the map. After little investment in the community facilities that this area of social housing needs, some developers are rebranding it ‘Upper Ouseburn’. Ouseburn – part of the city’s cultural quarter – is expanding, threatening the cohesion of a longstanding community and driving up rents.

Land in Shieldfield is also swiftly being developed into private student housing. With students only living there for a year, the area’s population is increasingly unstable, creating tension in the community. Student digs are seen as a way to hold the land for large-scale redevelopment later.

‘Often when you’re talking to local residents, [they say] the students are to blame, but there’s bigger things going on here.’

Alison Merritt Smith, Shieldfield Art Works

Shieldfield’s residents love their area. They compare it to Eastenders. The difference, though, is that Shieldfield lacks the communal spaces that allow Albert Square’s community to flourish. Without a residents’ or tenants’ association, it is also difficult for residents to make their feelings heard.

Shieldfield Art Works

A Methodist project is seeking to tackle these issues. Shieldfield Art Works (SAW) combines faith, art and community activism. Part church, part art gallery, part community space, SAW’s work builds community, showcases the area and stimulates the voice of residents on the issues affecting them.

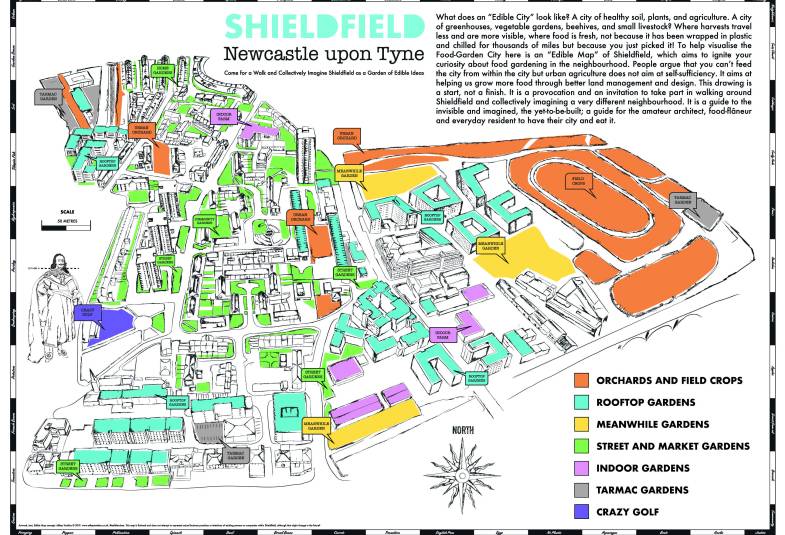

Guided by local residents, SAW produces art which highlights the issues being faced by the local area. Whether guerrilla-planting of wheat around the estate to provoke discussion on the use of public land, filming the stories of the residents, or putting on an exhibition of prints based around the culture of using housing as a commodity, their art expresses the hopes and anxieties of the local community. They also teach on a module at the university which brings students and the local community together, building bonds.

Based in the building of the former Methodist church, SAW is rooted in faith. The team is overseen by a minister, and observes a cycle of prayer and rest. They also run Mixing Bowl, a weekly fresh expression of church based around art. Those who take part really appreciate the welcome they get, often feeling excluded from more traditional church. Treating local issues spiritually, they perform a ‘funeral’ for each exhibition, reflecting on how it went and celebrating it. They aren’t simply protesting, but instead imagining a new, better world: God’s kingdom.

Treating housing primarily as a commodity is making it harder for many people to afford a home, but it’s also having a negative impact on communities. Churches are often the last community group left in an area. The Archbishop of Canterbury’s Commission on Housing, Church and Community is exploring how churches can better promote community – both by acting as a prophetic voice on issues which affect their area, and by fostering fellowship. SAW’s example shows how effective this can be.

Notes

- Shieldfield Art Works can be found here. Until 2019, it was known as The Holy Biscuit.

- SAW is part-funded by a Connexional grant from the Methodist Church.

- Pastoral oversight is provided by a Methodist minister, Rev Alison Wilkinson.

- Shieldfield Methodist Church was dormant before Rev Rob Hawkins made a deal with Ramy Zack, the owner of a large commercial art gallery nearby called The Biscuit Factory, who offered a philanthropic investment for it to be reopened as an arts and community space.

- The Holy Biscuit was opened in 2010.

- SAW has six employees, all working for approximately two days a week.